The anchorages of a style

In the mid-1980s Christian Liaigre exhibited his first furniture pieces in his showroom on the left bank, laying the foundations of an aesthetic vocabulary that aims to last.

See details.

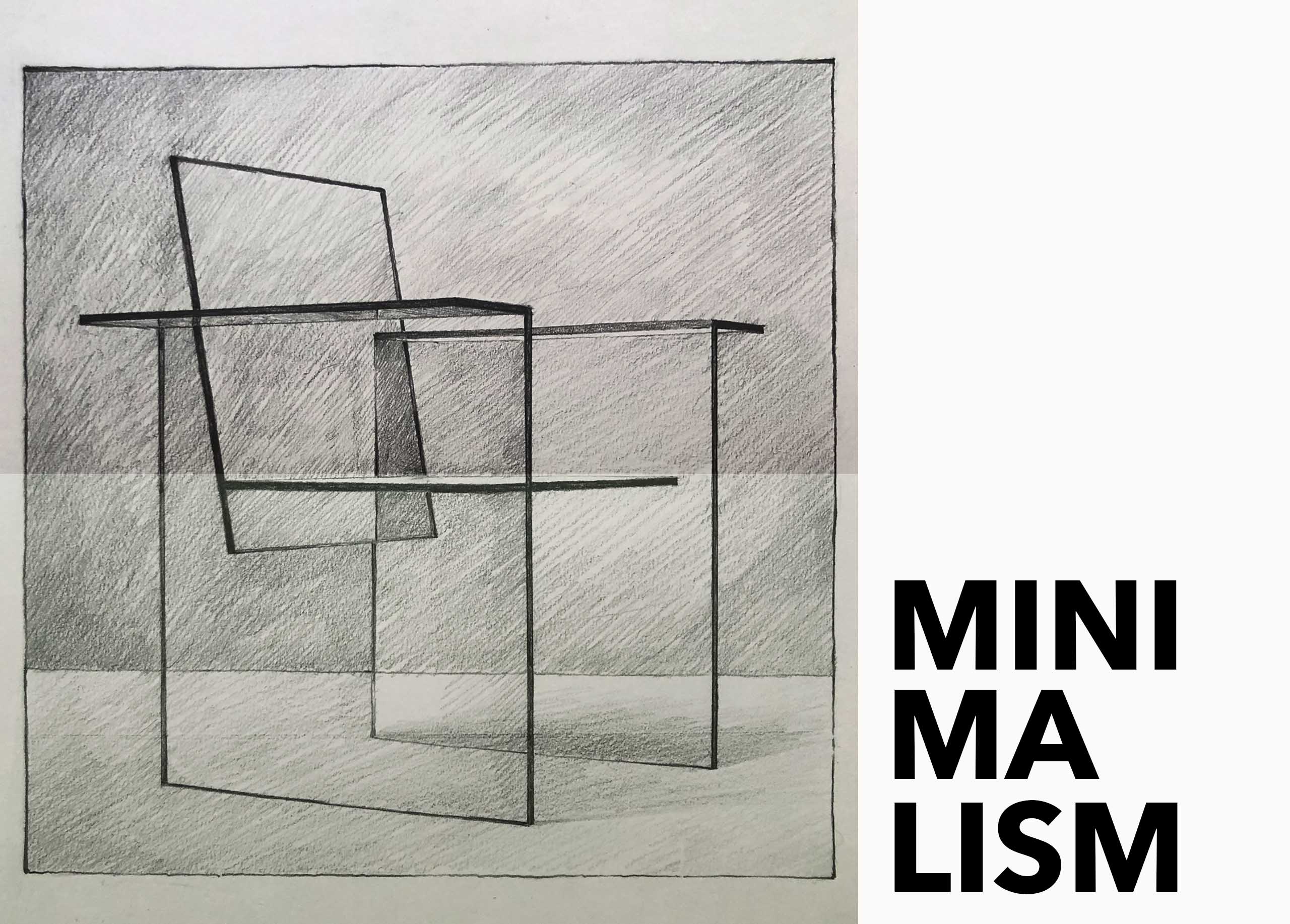

In the mid-1980s Christian Liaigre exhibited his first furniture pieces in his showroom on the left bank, laying the foundations of an aesthetic vocabulary that aims to last. Without yielding to the seductions of fashion, his furniture praises an apparent simplicity, imposing clean lines and classicism nourished by a solid culture, as a form of minimalism that contrasts with some of the trends of the time.

Texts: Françoise-Claire Prodhon

Close

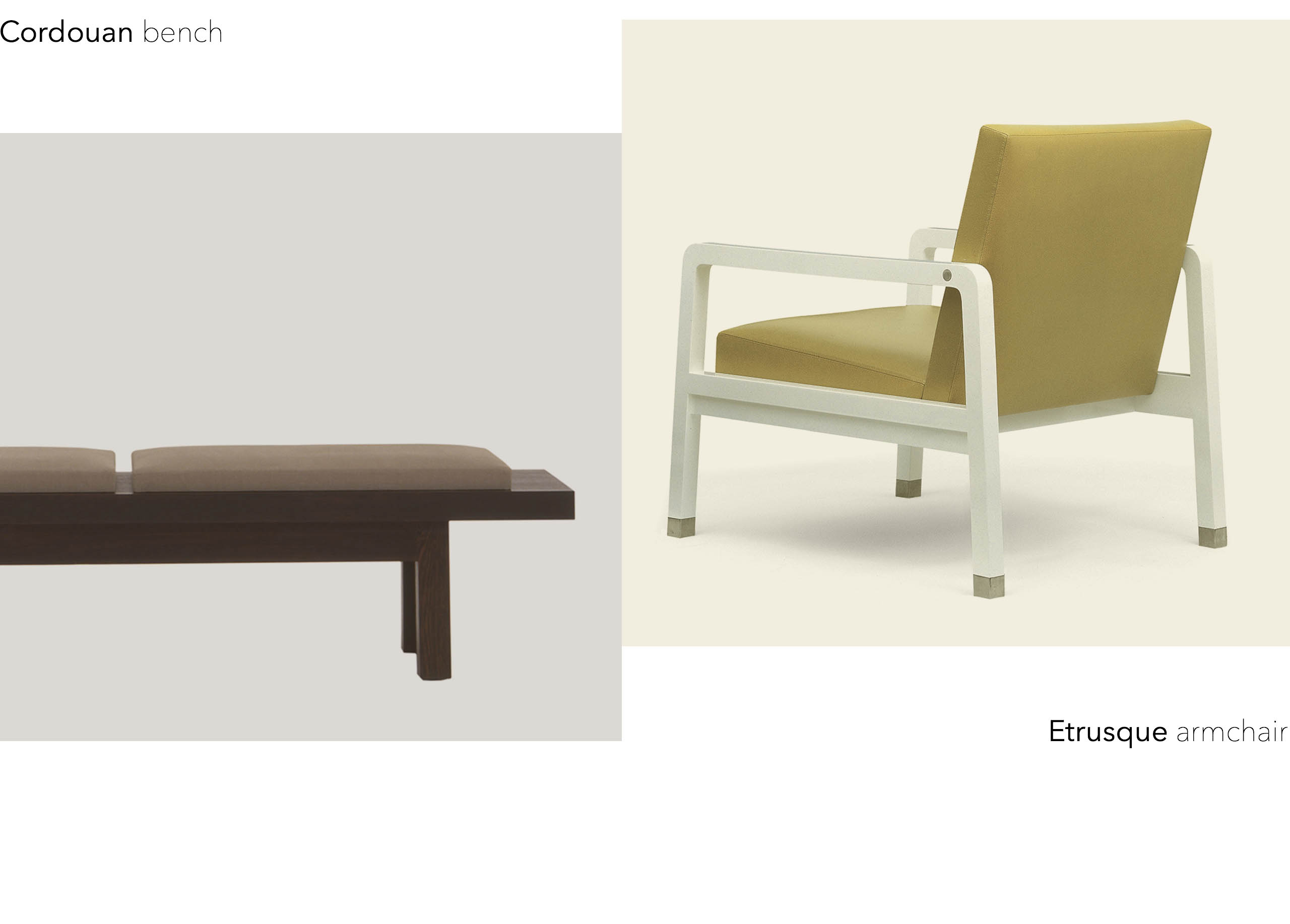

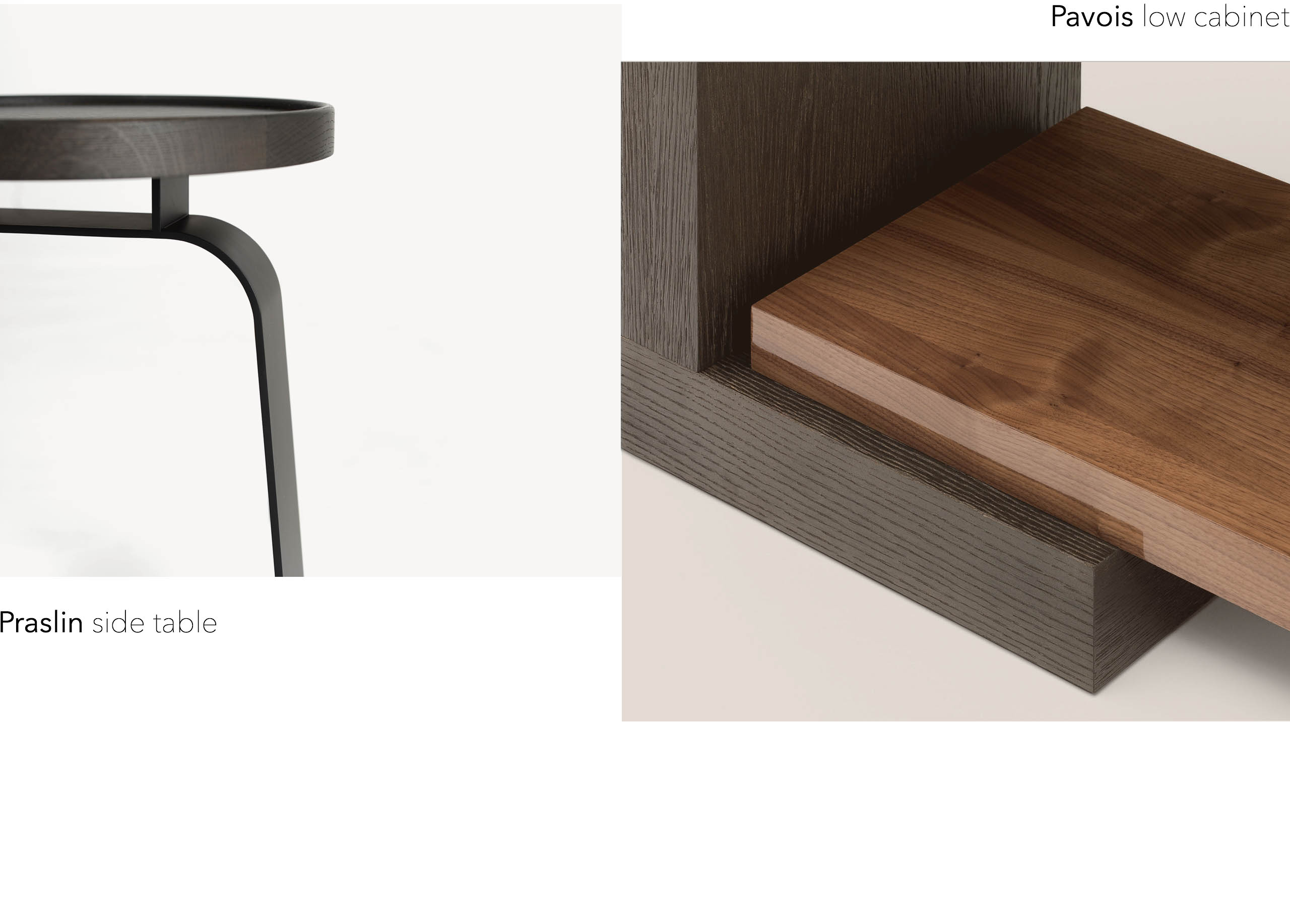

Behind the asceticism of lines and disinterest for the avant-garde, lies the conception of an art of life and living that suggests a concern for well-being. Above all, beyond stringency and restraint, Liaigre’s taste for noble and natural materials asserts itself, together with the craftsmanship that leads to a command of meticulous skills and extreme care that is given to every detail without giving way to anything superfluous.The beauty of each creation comes from quality: obviously that of the design, concept, materials, manufacture and finishes but also the generosity of proportions. Special attention is given to ergonomics, gestures, a feeling, the touch of the materials and textures, and what we call comfort in the broadest sense of the term.

This timeless style, unconcerned by fashion, does have references. It is on the contrary rich with multiple influences and inspirations, sustaining a free creative process that reveals itself over time, exemplifying itself in living spaces as well as in pieces of furniture.

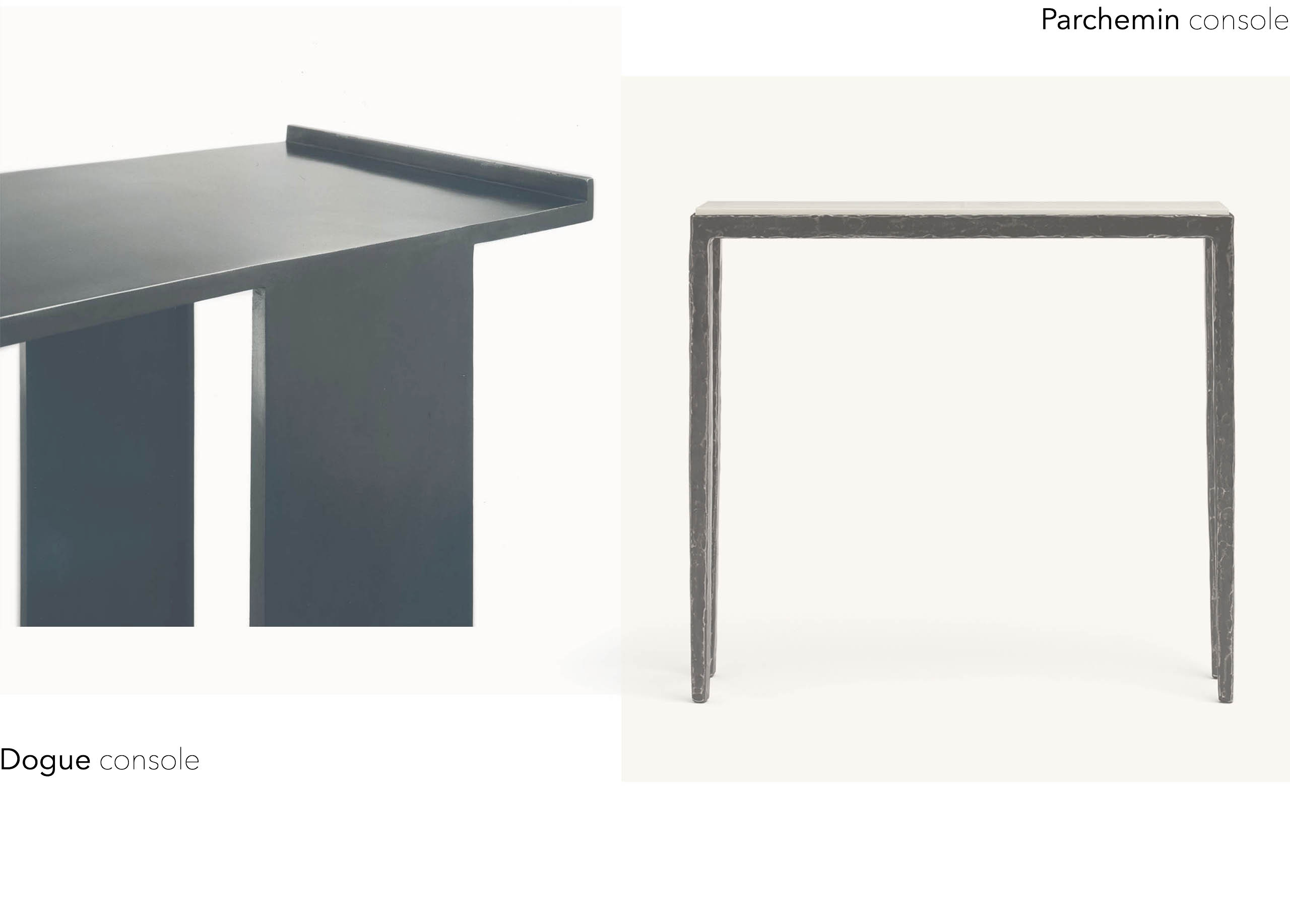

Synonymous with French taste, his unostentatious style based on exceptional know-how and furniture designing which is in line with the great cabinetmakers and interior decorators of the eighteenth century, as well as the Modernist creators of the 1930s. Finally, the radical use of simple forms and natural materials with a strong aesthetic and visual intent derives from the «Less is More» of Minimalism and the aspiration of getting to the essential.

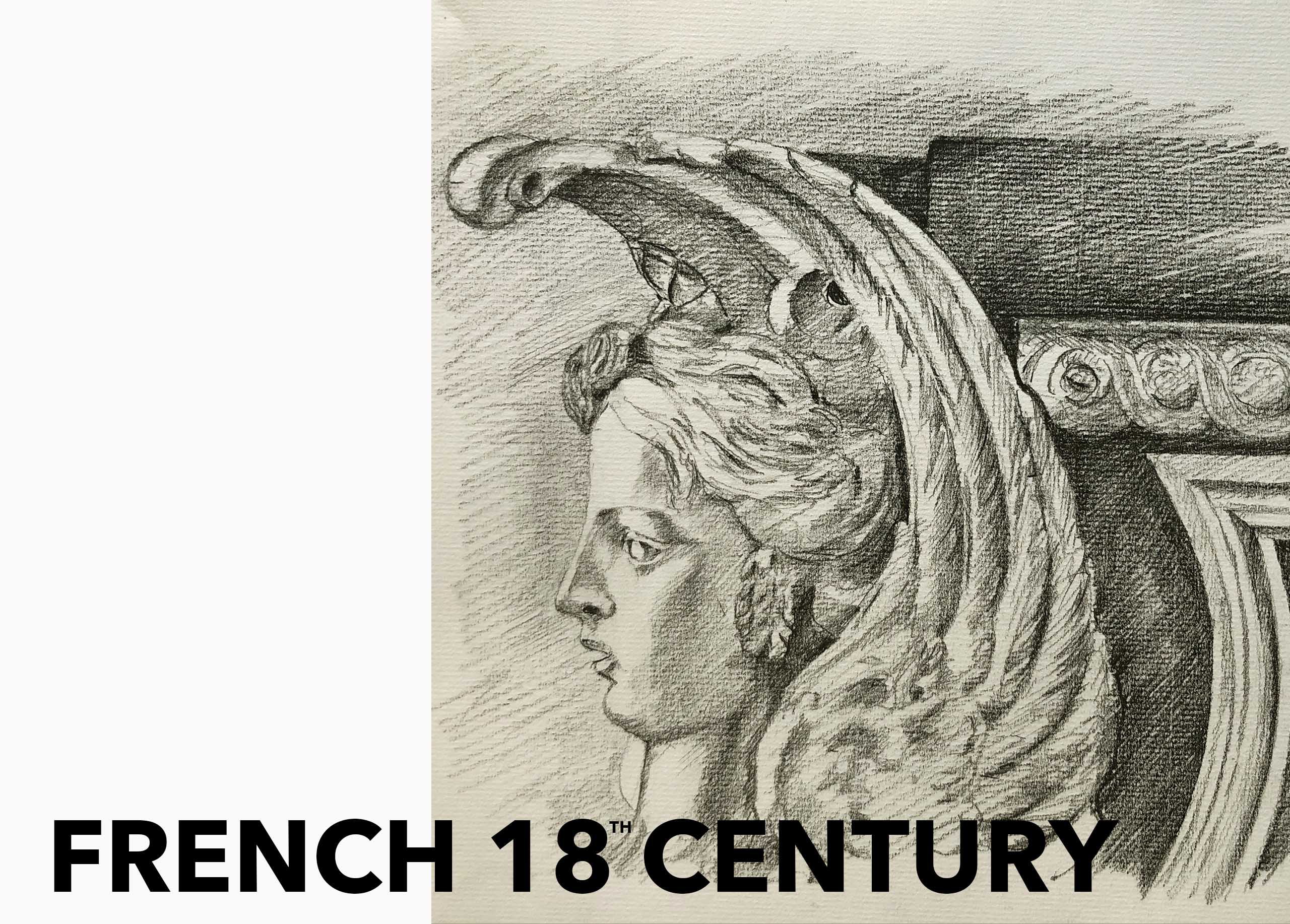

The 18th Century is a century of many paradoxes that opens with the austerity of the style of Louis XIII. Then from the reign of Louis XIV (1660-1715), we head towards a creative profusion confirmed under the reign of Louis XV. It comes to a peak with what will be called the Louis XVI style (from 1774 to the Revolution of 1789), during Louis XVI’s reign.

It is a century in which the French arts and crafts take on summits of refinement and craftsmanship, supporting an art of living which is undoubtedly reserved for a minority but which serves as a laboratory for a deeper reflection on what the habitat, its design and furnishings as a whole must offer.

Forgotten throughout the 19th century, the Louis XVI style inspired some of the greatest decorators of the 1920s-30s such as Ruhlmann, Frank, Ingrand, Dupré Lafon or Dunand,… It is not a question of their direct reinterpretation, but their view of the simplicity and elegance of Louis XVI furniture, as well as the refined choice of materials, finishes and upholstery which profoundly influence their conception of furniture. Alabaster, leather, Galuchat leather, verre églomisé, lacquer and parchment. The materials used to ornate the decorators’ work require a meticulous expertise and a technical mastery that make their creations jewels in the history of the decorative arts. The Louis XVI style brings comfort with its formal precision, that meets the aspirations of the beginning of the 20th Century. This classical heritage allows them to develop a repertoire of forms that are as timeless as they are modern.

The French 18th century invented the notion of comfort in absolute luxury, multiplying the kinds of seats and tables destined for all kinds of uses and temporalities. This is how a lot of chairs such as the Bergère parlor chair, the loveseat, the sofa and the daybed were created. Their seats and backrests offer ideal ergonomics for work, embroidery, board games, reading, rest, and receptions.

...

For any French decorator, the knowledge of the 18th Century art of living is a fundamental cultural background. At Liaigre this inspiration passes through the filter of the great decorators of the early 20th century, previously mentioned. There is an obvious link between the late 18th Century Louis XVI furniture, the great Modernist designs of the 1920s-30s and the refined style developed by Christian Liaigre and his studio since the mid-1980s. Once again, Liaigre follows in the footsteps of tradition and a state of mind, but not as an imitator seeking to perpetrate well-identified forms. What draws Liaigre’s attention to the French 18th Century is primarily “efficiency”. Careful thought has to be given to utility and being functional. Consequently, ergonomics is fully analyzed to ensure comfort and freedom of movement.

How can we avoid speaking about the way of associating sober lines with noble materials and sophisticated finishes, to reveal artisans that owe everything to a tradition strongly anchored in the 18th Century, enrichened with time, and innovation. The dialogue between precision and luxury is synonymous with elegance. The Liaigre style likes to define itself more as an art of living in a broad sense, than as a style. Its demands and precision make it necessary to consider the design of a space to the slightest detail. This includes the continuation of a quest for beauty, expressed by the greatest designers of the 18th Century.

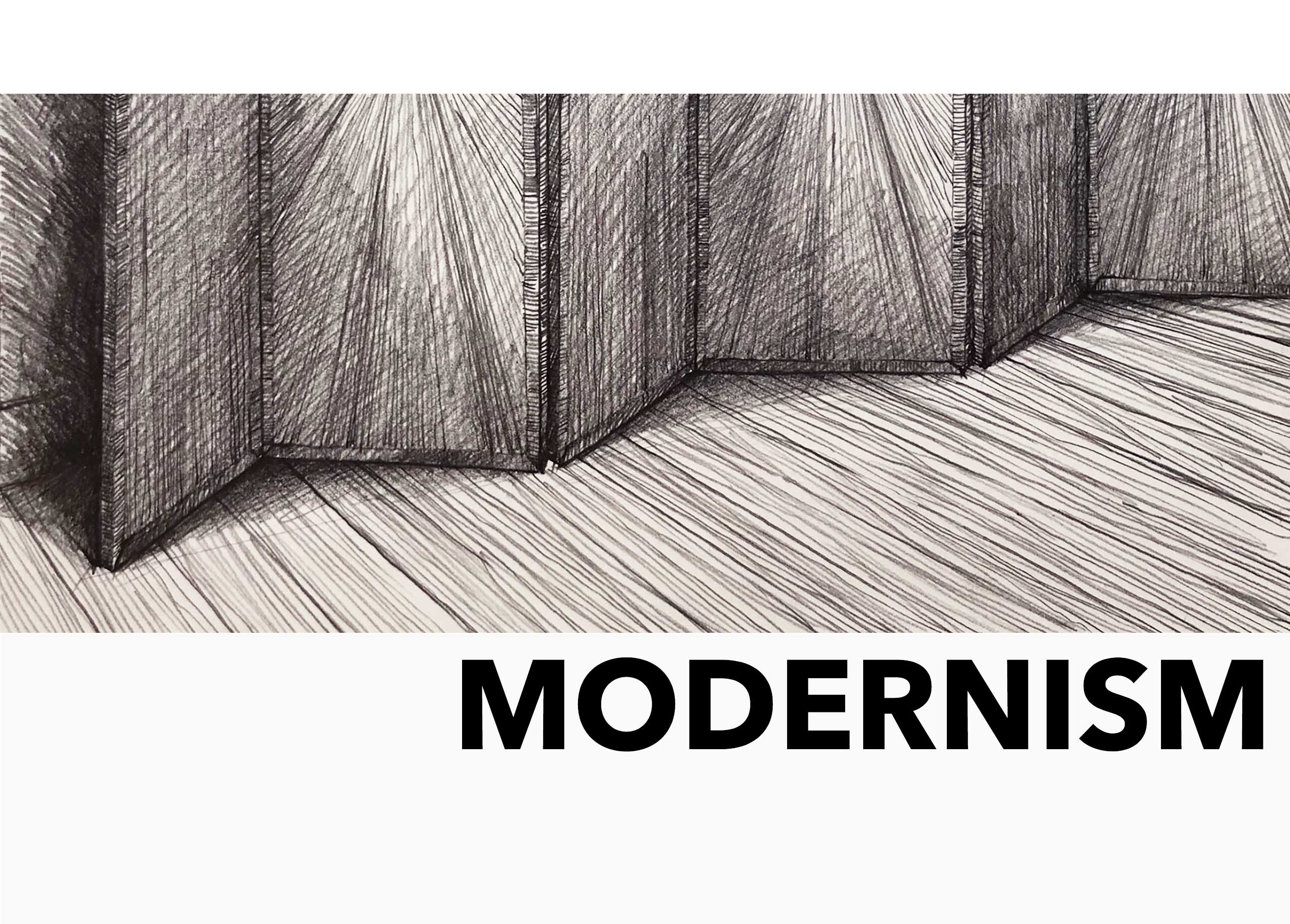

Liaigre’s style which has been inspired by many sources, asserts itself over the years. Nurtured by an attachment to the tradition of French cabinet workers and arts and crafts that it constantly enrichens, and a receptivity to influences from afar, whether it be distant in time or geographically speaking. Modernism, this special moment of the beginning of the 20th Century, during which architecture, decorative arts, painting and sculpture are reinvented in a vocabulary that breaks away from the decorative and ornamental excesses of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It has been one of Liaigre’s main sources of inspiration and reference from the very beginning.

The International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, which took place in Paris in 1925, coincided with the peak of Modernism, but this international movement began shortly before 1910. Its beginnings in France were first expressed in painting and sculpture: Picasso’s painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon ( 1907) marked a decisive turning point. This work announces the appearance of Cubism which develops between 1907 and 1914 of which Pablo Picasso is one of the founders (with Georges Braque). Cubism imposes a new vision of landscape and domestic space, it fragments nature and objects creating an image that simultaneously reveals all aspects. From this unprecedented pictorial space, the spectator most often perceives only a composition constructed from lines, angles and superimposed planes. The cubist space develops and is built like architecture and its aesthetic influence will very quickly go beyond the single domaine of art, bringing architecture and design in its wake.

Simplicity of forms, clarity of lines, the desire to go to what is essential, sophisticating materials (wood, bronze, lacquer), since it originated, Liaigre’s style echoes and extends the aesthetic quest of some of the greatest Modernist architects and decorators of the 1920s, such as Jean-Michel Frank, Pierre Chareau or Paul Dupré Lafon. In their day, they were able to imagine living spaces, pieces of furniture and lighting that fit but also a richness of architectural details that make every-day life easier. This global approach to the art of living resonates particularly in the way Liaigre approaches its design and decoration projects, such as its furniture designs or accessory lines. The individual and his feelings are at the heart of this approach. This conception of architecture and design is thus one of the characteristics of Liaigre’s spirit which has contributed strongly to its success.

.

The aesthetic language of Liaigre is based on a solid visual culture as well as a great knowledge of the history of forms, far beyond the repertoire of architecture and design. From these numerous inspirations, sometimes quite paradoxically an unidentifiable writing is born. Long before the word «minimalism» was used to describe any aesthetical trend, the desire to go to the essential is expressed in the work of many avant-garde artists at the beginning of the 20th century.

This quest for a refined design goes hand in hand with the claim for creative freedom that can be summed up by the desire to move away from a supported realism. This «illusionist» realism intended to create something truer than nature and imitate reality as closely as possible and has been one of the major challenges of artistic creation for centuries. But this need dropped back with the invention of photography in 1826. Little by little, art breaks away from constraints and develops a creative field that allows for aesthetical research that gradually frees itself from the question of resemblance or credibility. The beginning of the 20th century saw the emergence of a large number of artistic trends that are equally «laboratories» of creation. Sculpture which for centuries was subject to ancient models and allegorical or commemorative duties, embarks on the path of an unprecedented modernity.

If undeniably Liaigre’s style is given the Minimalist inflection, firstly we cross vocabulary often used by those who wrote and commented on the projects and creations of the House. Sober, reserved, simple…are some of the words most often used to describe Liaigre’s style. We need to state that none of these adjectives is false, or betrays the spirit developed by Christian Liaigre since the very beginning, which continues in the creative studio today. It is also referred to as a “style without the impact of style” a formula which means that there is no excess of writing or gesticulation in Liaigre’s vocabulary. Everything is thought out and drawn with a view to correctness by always reconciling notions of harmony and ergonomics. These delightful aesthetics, are dictated more by imperatives than minimalism (excess is the opposite of what the House has been developing for 40 years), but above all by a reflection whose central point is the human factor (use, feeling of well-being, comfort, softness).

.

Discover other

Portrait 1